2026-01-29

When people talk about accessibility in digital design, they often focus on physical needs like making sure websites work with screen readers or that buttons are large enough to tap. These considerations are essential, but they don’t tell the whole story.

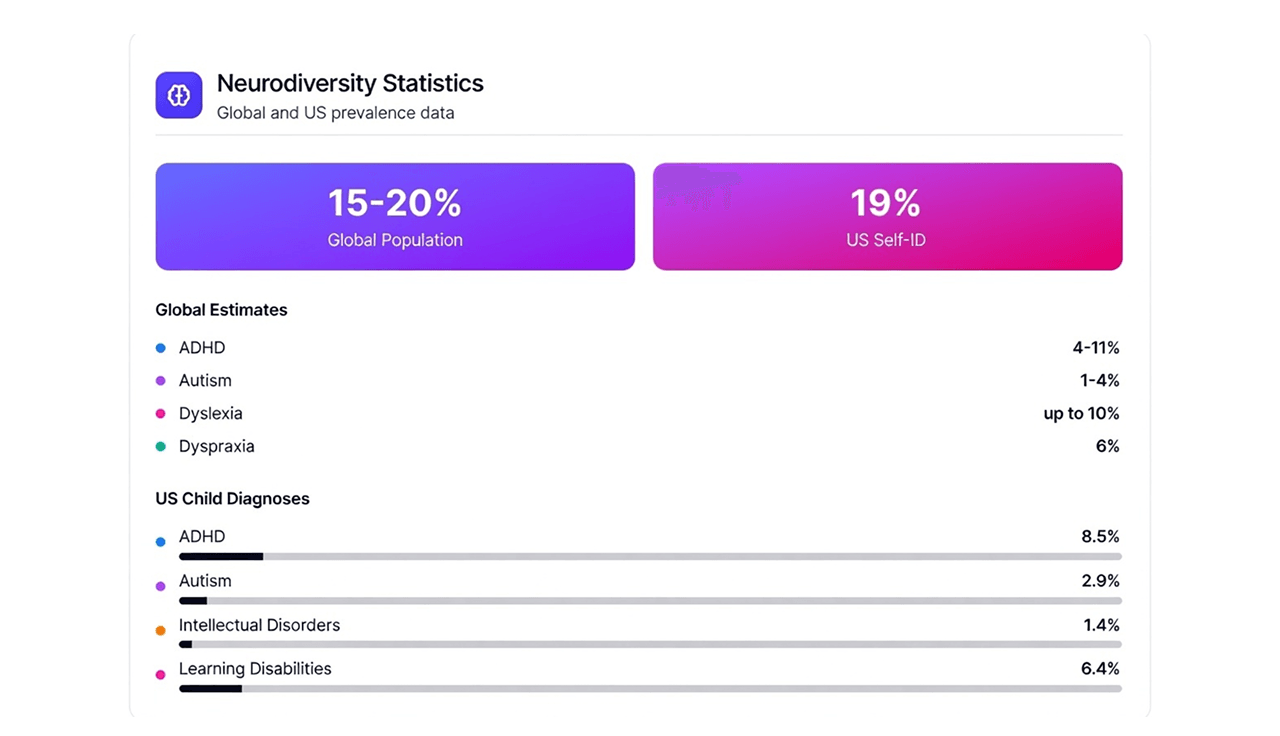

A significant portion of the population lives with cognitive or neurodevelopmental disabilities, such as ADHD, autism, dyslexia, and memory impairments. Globally, about 15 to 20 percent of people are neurodivergent, and nearly 1 in 5 adults in the US identify this way [1]. In Canada alone, it is estimated that 27% of the population has a disability, with a vast number of these related to learning, memory, or mental health. For these users, the barrier to entry isn't necessarily seeing the screen; it is processing the information upon it . This shows that cognitive accessibility is not rare and should be a basic part of digital design.

Refer source Here

Refer source Here

Designing for neurodiversity means paying close attention to cognitive effort. Instead of only asking, “Can users access this?” we should also ask, “How hard is this to think through?” Principles like Chunking and Hick’s Law [2] can help designers create calmer, clearer experiences that support focus, reduce stress, and respect different ways of thinking.

1. Chunking and Executive Function: Designing for ADHD

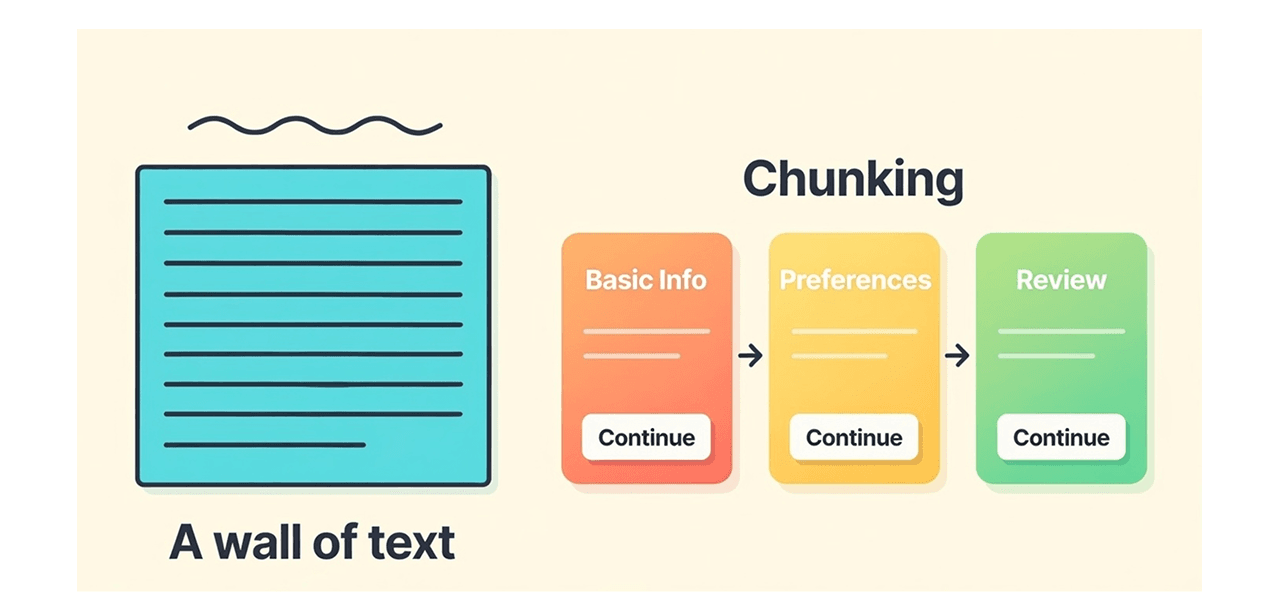

One of the primary challenges for users with ADHD is the regulation of dopamine and motivation. Research indicates that ADHD is linked to issues with dopamine regulation, making it difficult for users to "start tasks, stay focused, or know when to stop". When a user with executive dysfunction encounters a "wall of text" or a massive form, the cognitive load (the mental effort required) spikes, often outpacing their motivation to complete the task [3].

The solution lies in the psychological concept of Chunking. Chunking means dividing information into smaller, clearly labeled sections so it’s easier to understand. Instead of presenting everything at once, content is broken into logical parts that users can move through step by step.

For example, rather than showing a full account setup form on one screen, a product might guide users through short steps like “Basic Info,” “Preferences,” and “Review.” Each step feels achievable on its own. This approach is directly related to progressive disclosure, where only the most relevant information is shown at any given time. For neurodiverse users, this turns an overwhelming task into a series of small wins, making it easier to stay engaged.

2. Predictability and Defaults: Reducing Decision Fatigue and Anxiety

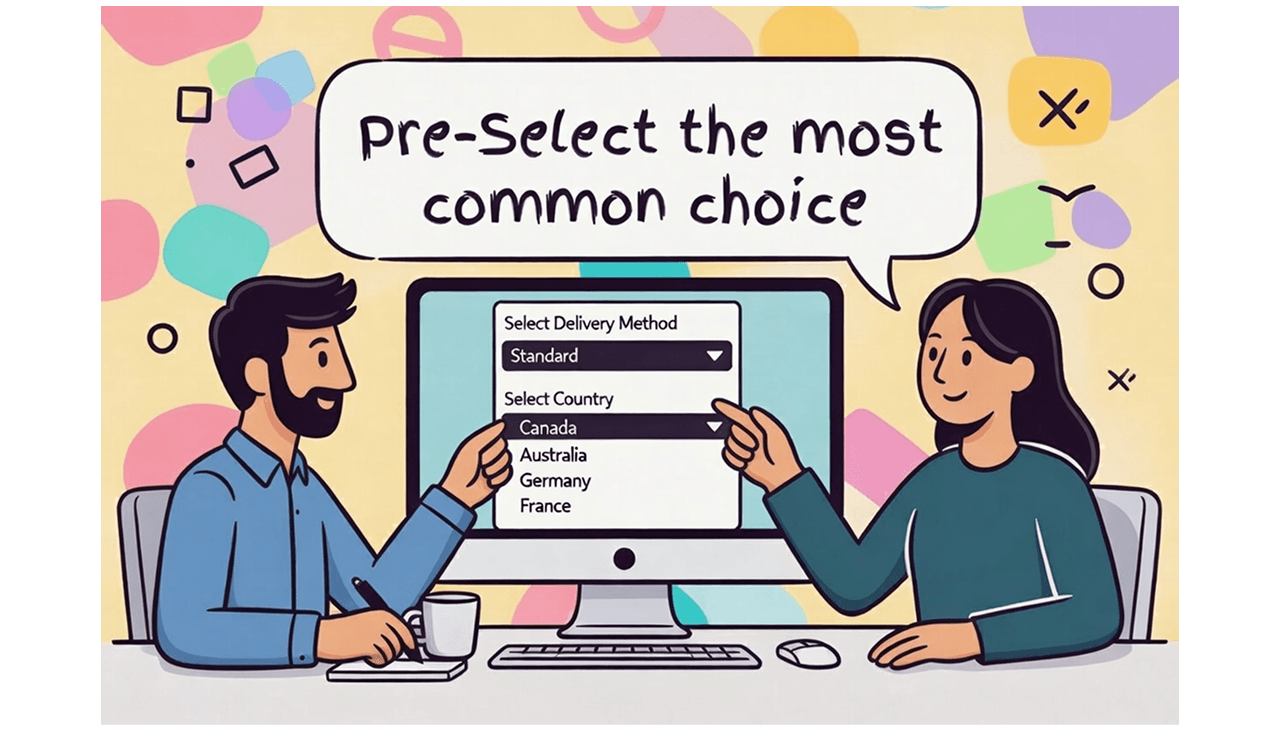

Decision-making is an expensive cognitive process. Hick’s Law states that the more options a person sees, the longer it takes them to choose and if the options are too numerous, they may not choose at all.

For users with anxiety or autism, an abundance of ambiguous choices can be overwhelming. Autistic individuals often prefer communication that is "clear and unambiguous" and feel more secure when they have control over their progress. Unpredictable interfaces or "surprise" interactions can disrupt this sense of security.

To support these users, designers should use Defaults wisely. Pre-selecting a standard option (like a delivery method or country) reduces the friction of decision-making. Defaults act as a safety net; they signal to the user, "This is the standard path; you don't have to overthink this." Furthermore, consistency is key. Interface logic should be "unambiguous and precise," aligning with the strengths of autistic users who often value structure and logical flow. If a navigation menu changes location or style from page to page, it forces the user to relearn the interface constantly, draining mental energy that should be reserved for the task at hand.

3. Feedback Loops: Countering Memory Issues and Uncertainty

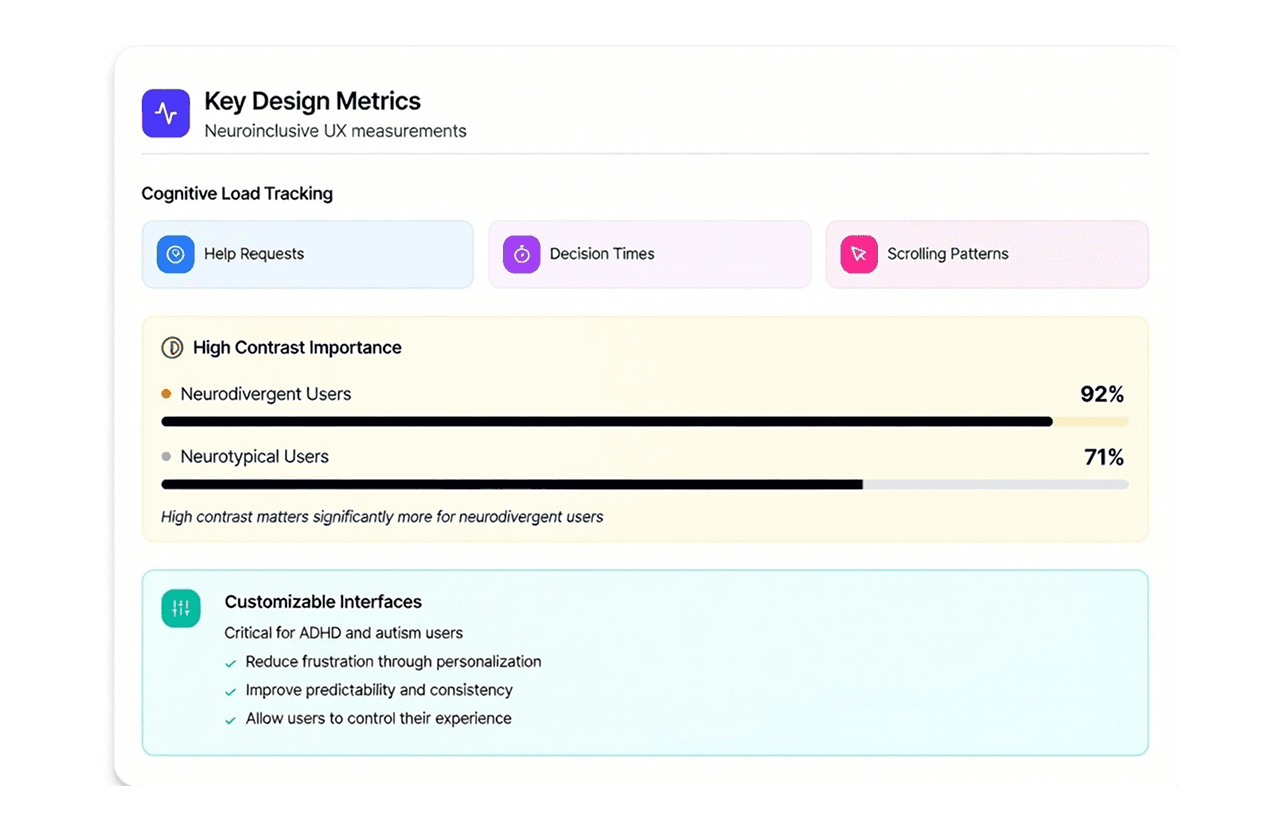

For users with memory impairments which make up approximately 18% of disabilities in some demographics or those experiencing high cognitive load, working memory is a scarce resource [4]. Uncertainty blocks decisions. If a user clicks a button and nothing happens immediately, anxiety sets in: Did it work? Did I make a mistake? Neuroinclusive UX also looks at signs like how often users ask for help, how long they take to decide, and how they scroll. Research shows that high contrast is important for 92% of neurodivergent users, compared to 71% of neurotypical users [5]. Customizable interfaces also reduce frustration and make interactions more predictable for people with ADHD and autism, helping them feel more in control.

Refer Source Here

Refer Source Here

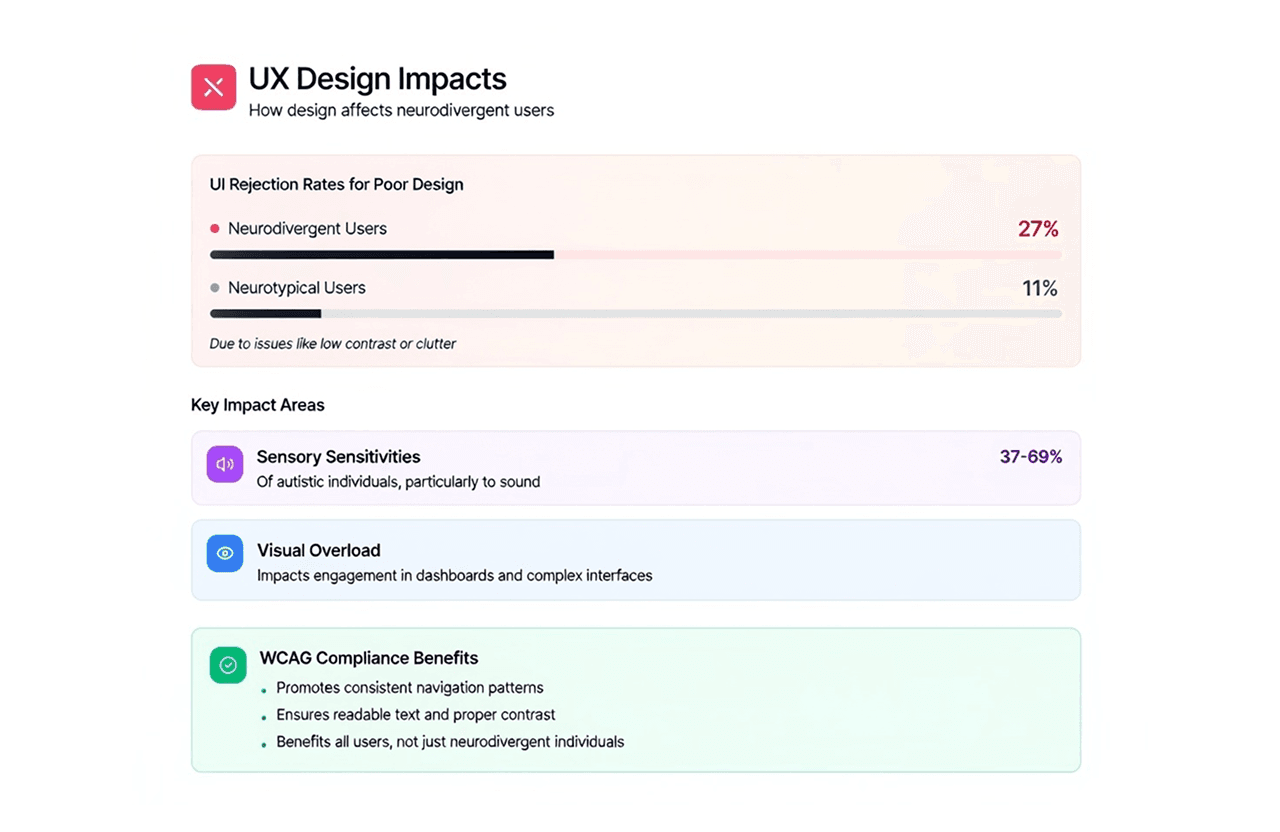

Poor design has real consequences: 27% of neurodivergent users abandon interfaces due to issues like clutter or low contrast, compared to 11% of neurotypical users. Sensory sensitivities affect 37 to 69% of autistic individuals, making visual and auditory overload especially harmful in complex dashboards.

Refer source Here

Refer source Here

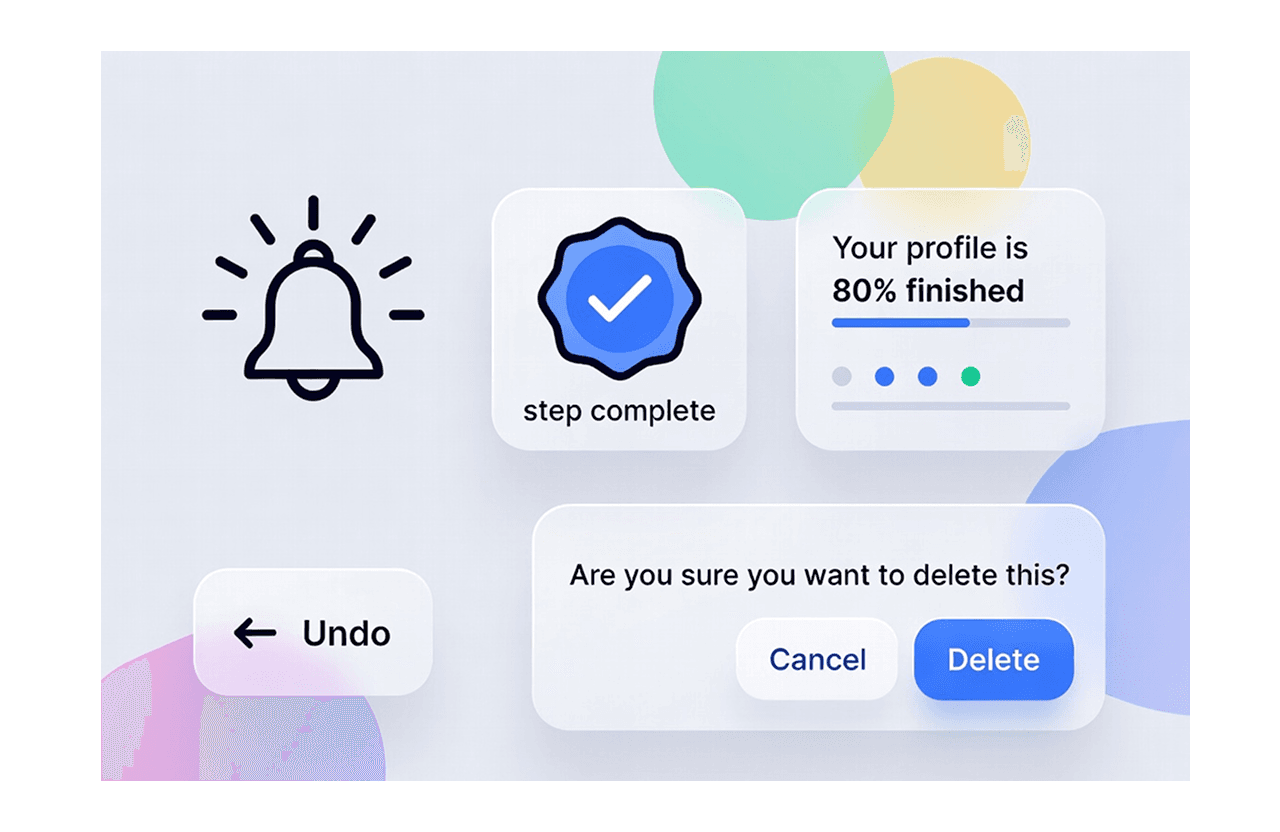

Providing immediate feedback and reassurance is critical. Whether it is a celebratory chime, a "step complete" badge, or a notification stating "Your profile is 80% finished," positive reinforcement keeps the user grounded in the process.

This concept extends to Tolerance for Error. Users should feel safe knowing they can make a mistake without catastrophic consequences. Features like "Undo" buttons or confirmation messages (e.g., "Are you sure you want to delete this?") reinforce user trust. For a user with dyslexia who might misread a label, or a user with ADHD who might impulsively click the wrong button, the ability to revisit decisions reduces the pressure of the interaction.

Conclusion

While these principles are especially helpful for neurodiverse users, they improve the experience for everyone. Around 15 to 20 percent of people worldwide are neurodivergent, which means cognitive accessibility is not a special case. On top of that, anyone can experience reduced focus due to stress, tiredness, or distractions. Designing with clear structure, readable layouts, and helpful feedback lowers mental effort for all users. Simple choices like good contrast, predictable navigation, and clear confirmation messages reduce confusion and prevent users from giving up. Neuroinclusive design is not just about support. It is about creating digital experiences that feel easier, calmer, and more human for everyone.

At Rootcode, we help teams audit, design, and implement accessibility improvements that meet WCAG 2.1 and European Accessibility Act requirements. From identifying gaps to delivering inclusive, compliant digital experiences, we support you every step of the way. Book a free consultation today and make your digital products accessible, inclusive and prepared for the future.